In Praise of Guessing

Last night at the Lean Product Meetup someone asked me, “How do you set Key Results when you don’t have a baseline?”

I replied, “You guess.”

People hate that answer. But it’s the only possible answer. You can try to dig up numbers on competitors, or similar products, but the reality is that in the end you have to guess. It’s an informed guess, hopefully, but it’s a guess and you have to treat it as one.

The word “guess” makes people deeply uncomfortable. We’ve been trained to believe that business is about certainty, about knowing things. About data-driven decisions. But early in any endeavor—whether setting OKRs for a new initiative or estimating how long a feature will take to build—you don’t have data. You have hunches. You have analogies. You have experience with vaguely similar situations.

You have a guess.

Engineering Estimates Are Guesses Too

This isn’t just true for Key Results. It’s true for engineering estimates. At the start of a project, engineers are asked how long something will take, and they provide a number. That number is a guess dressed up in a spreadsheet.

What’s interesting is that these guesses get better. Way better. As the project progresses and the team learns the codebase, understands the edge cases, and runs into the unexpected complexities, their estimates become more accurate. By the time you’re close to shipping, you can predict with reasonable precision when you’ll be done.

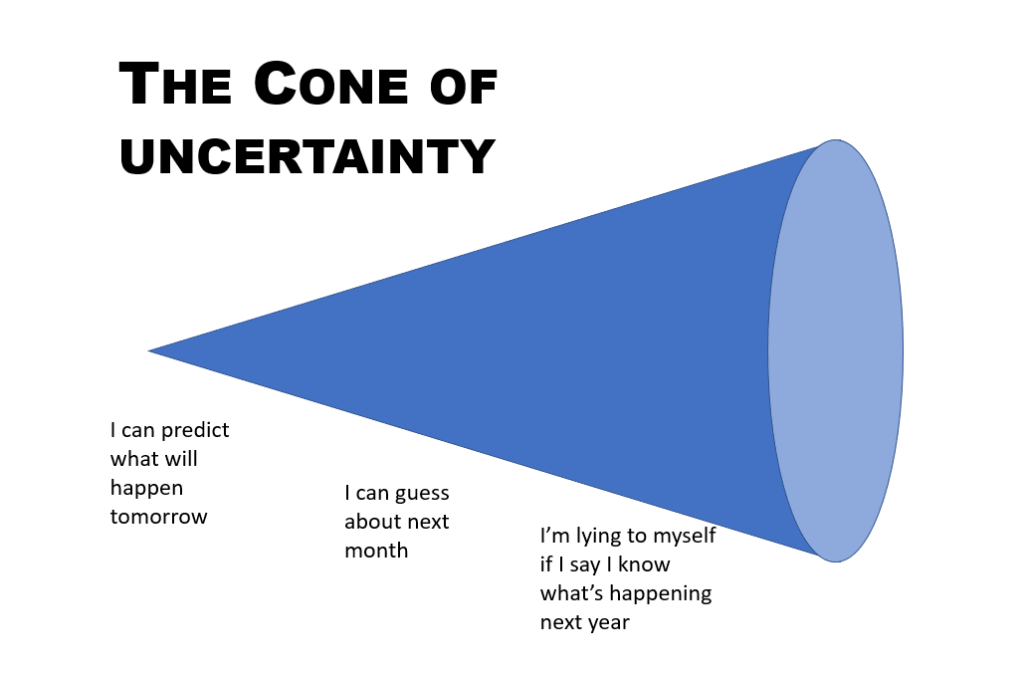

The Cone of Uncertainty, anyone? That’s exactly what it describes: estimates are wild guesses at the beginning and converge toward accuracy as you approach completion.

The Cone of Uncertainty, anyone? That’s exactly what it describes: estimates are wild guesses at the beginning and converge toward accuracy as you approach completion.

So why do we pretend otherwise?

Prediction Is a Skill

James Lang, in his book Small Teaching, tells a story that changed how I think about this. He went to the same coffee shop every day and ordered the same tea from the same barista. Every single day, he told her his order. And every single day, she’d forgotten it.

One day, instead of telling her, he said: “Guess.”

She guessed wrong. But after that, she always knew his order.

This is how memory works. Prediction cements learning in a way that passive reception doesn’t. When you guess and then find out you were wrong, your brain pays attention. It updates its model. The error sticks.

This is the same mechanism at work when students take quizzes (retrieval practice) or use spaced repetition. You force your brain to make a prediction, then give it feedback. Over time, your predictions get better.

Guessing isn’t a failure of knowledge. Guessing is how you build knowledge.

Building Product Intuition

When teams set Key Results without baselines, they’re making predictions about how the world works. “If we do this thing, we think this number will move by this much.” Then they ship, measure, and learn.

Some teams hit their Key Results. Many don’t. But here’s what’s interesting: over time, the experienced ones get eerily good at predicting what will move the numbers. They look at a proposed feature and say, “That won’t work,” or “That’s going to have a bigger impact than you think.”

That’s not magic. It’s compressed experience. It’s the result of making predictions, being wrong, paying attention, and updating their mental models over and over again.

This is why you want senior people on your team. Not because they’ll work all night (they won’t—they have lives). But because they’ve been wrong enough times that they can now be right. They’ve built intuition through prediction.

The Problem With Punishing Bad Guesses

Here’s where organizations go wrong: they punish inaccurate estimates.

Miss your Key Results? You failed. Come in late on a deadline? You’re bad at estimating. Your prediction was wrong? You should have known better.

This is exactly backwards.

When you punish bad guesses, you get one of two outcomes:

- Sandbagging: People pad their estimates until they’re guaranteed to hit them. Engineering says six months when they think it’ll take three. Product sets Key Results so low they’re meaningless.

- Avoiding accountability: People refuse to commit to any number. Everything becomes “it depends” and “we need more research.” Decision paralysis sets in.

Neither of these helps you build the organizational intuition you need to make good decisions. You need people to make real predictions—their actual best guesses—and then learn from the results.

The sooner we stop pretending estimates are accurate, the better off we’ll be. Estimates are guesses. Good guesses. Educated guesses. But guesses. And making them, getting them wrong, and updating is how you get better.

Why Mixed-Age Teams Matter

This is one reason why the best teams mix experience levels. Silicon Valley has a weird obsession with youth—the mythology of the young founder working out of a garage. But the truth is that a great team has people who’ve made different kinds of guesses.

The junior person brings energy, recent technical training, and fresh perspectives. They haven’t learned yet what “won’t work.”

The senior person brings a library of past predictions and their outcomes. They’ve watched features fail. They’ve seen markets shift. They’ve been wrong in specific, memorable ways that inform their current judgments.

Put them together and you get something neither could achieve alone: ambitious new ideas tempered by pattern-matched wisdom. The senior person learns from the junior person’s fresh approach. The junior person absorbs years of compressed experience through osmosis.

But this only works if both are allowed to guess—and allowed to be wrong.

Making Guessing Safe

So what do you do with this?

If you’re a leader: create an environment where guessing is safe. When someone misses a Key Result, the conversation isn’t “why did you fail?” It’s “what did we learn? What does that tell us about how to set the next one?”

When an engineering estimate is off, don’t ask “why didn’t you know?” Ask “what did we discover that we didn’t expect?” That’s where the learning lives.

If you’re an individual contributor: guess bravely. Make real predictions, not sandbagged ones. Write them down so you can learn from them. When you’re wrong, pay attention to why. Your wrong guesses are building your future intuition.

If you don’t have a baseline for a metric you want to track, just guess. By the end of the quarter, you’ll be a lot smarter about what that number should be.